The term “critical thinking” is widely used in education, especially in Career and Technical Education (CTE), and is a long-standing element of the Career Ready Practices; the standard is as follows:

Utilize critical thinking to make sense of problems and persevere in solving them.

Educators, policymakers, and curriculum developers frequently promote critical thinking as a goal, yet there’s little agreement on what it actually looks like in practice—or how students develop it and how success is measured.

Critical thinking is associated with higher-order cognitive skills such as reasoning, analyzing, evaluating, and problem-solving. In a workforce increasingly shaped by automation, employers value these skills because they can’t easily be replaced by machines.

Despite its prominence, the term is not clearly defined across educational settings. Some treat it as the ability to question assumptions or form logical arguments, while others view it as the process of decision-making under complex conditions. Consistently, the goal in CTE is to perform a technical task in a standard way, quickly and safely. This seems counter to thinking critically. Therefore, one aspect of critical thinking in CTE to knowing when to use it.

Critical thinking is not a single skill that can be taught in isolation. It develops through rich, sustained student projects that encourage inquiry, problem-solving, and reflection. When classrooms still rely on rote tasks or rigid procedures, they leave students little room to practice or grow these skills authentically. Without intentional instructional design—such as open-ended problems, collaborative projects, or performance-based assessments—students may not get meaningful opportunities to develop critical thinking.

Perhaps the biggest issue is that critical thinking is hard to measure. Unlike technical skills that can be assessed through checklists or performance tests, critical thinking requires evaluating a student’s thought process, decision-making, and ability to justify choices. Most standardized tests do not capture this well. As a result, success is often judged anecdotally or through vague descriptors like “shows improvement” or “thinks critically,” without specific evidence.

While critical thinking is a powerful educational goal, its popularity outpaces clarity. Without clear definitions, instructional strategies, and assessment tools, it’s challenging to ensure that students are truly developing and demonstrating this essential skill, especially in hands-on, fast-paced CTE environments where critical thinking matters most. The following list defines critical thinking with several specific adjectives — consider it the specific details of critical thinking. These can be used to revise lessons and create assessment rubrics.

Process-Oriented – Follows clear steps to solve real-world problems

Productive – Stays focused and gets things done

Precise – Pays close attention to details and aims for accuracy

Persistent – Keeps trying, even when the task is hard

Prepared – Plans ahead and is ready to work

Perceptive – Notices important details and makes connections

Probing – Asks good questions and looks deeper into the problem

Preventative – Thinks ahead to avoid problems

Precautious – Stays alert to risks and acts safely

Pioneering – Tries new ideas and isn’t afraid to explore

Persuasive – Shares ideas clearly and explains them with confidence

To effectively teach and assess critical thinking, especially in Career and Technical Education (CTE), it’s essential to translate abstract traits like “perceptive” or “productive” into observable behaviors that students can demonstrate—and instructors can measure.

Here’s is an example of critical thinking traits in student behaviors and tie them to rubric criteria for feedback and evaluation:

Example: Perceptive Thinking

Observable Behaviors:

- Observes and interprets details that impact decision-making (e.g., signs of wear on a part, irregular measurements)

- Connects technical data to project goals

- Justifies choices with evidence or reasoning

| Level | Description |

| 4 – Advanced | Accurately interprets relevant details and justifies decisions with strong reasoning |

| 3 – Proficient | Notices key details and explains decisions with logical support |

| 2 – Developing | Observes some details but reasoning is weak or unclear |

| 1 – Beginning | Misses important details or struggles to explain choices |

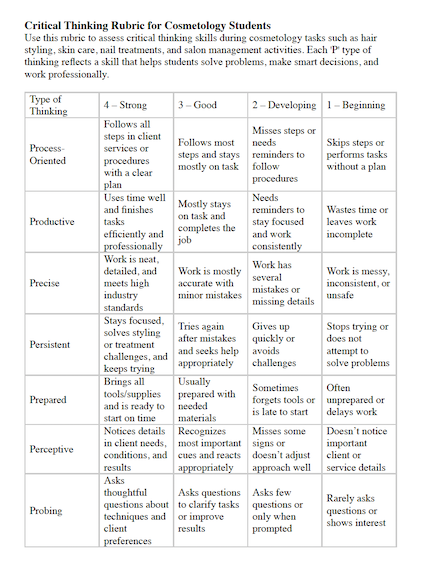

Click the image on the right to download a sample rubric for Cosmetology. You can easily revise this for your CTE program in and Generative AI app.

Summary:

The blog explores the widespread use of the term critical thinking in education—particularly in Career and Technical Education (CTE)—and highlights the challenges of defining, teaching, and assessing it effectively. While critical thinking is valued for its role in problem-solving and adaptability in today’s workforce, it often lacks clear implementation in classroom practice. The article emphasizes that critical thinking must be intentionally developed through inquiry-based learning and meaningful projects, not rote tasks. To bring clarity, the blog introduces a student-friendly framework of 11 “P” traits—such as Perceptive, Persistent, and Process-Oriented—that represent observable thinking behaviors. These traits can be used to revise lessons and develop practical rubrics for giving feedback and measuring student growth in real-world CTE environments.