Today I was thinking about instruction while modifying my online graduate course in instructional design. I feel extra pressure teaching a course to other educators on instructional design because the implied perception is that if you’re going to teach design practices and design, your course should model a great design. Therefore I carefully craft my objectives and design rubrics to assess student work. I scale back content to only what is essential to read and Intersperse videos for acquiring knowledge.

All effective teachers constantly think about how to tweak their lessons to increase student engagement and achievement. As I was updating this online course, how could I make the course more engaging and relevant to the student’s needs?

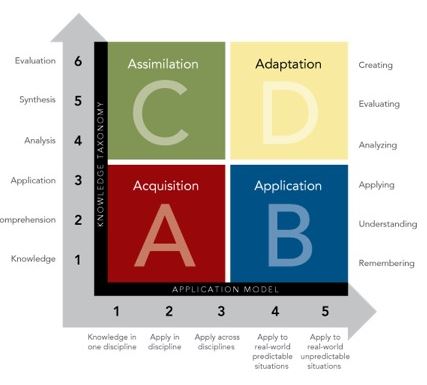

I reflected on the Rigor /Relevance Framework from the International Center for Leadership in Education. I have experience with the R/R Framework since much of my early writing was explaining how to use the framework in planning instruction and assessment. The framework’s four quadrants of teaching and learning distinguish between high and low rigor and high and low relevance. I want to push my instruction to Quadrant D, High Rigor/High Relevance.

I also read today about some of the current work of a not-for-profit organization called the Right Question Institute. This organization and many outstanding teachers are constantly looking for ways to increase the rigor of their instruction by moving from being focused on the right answers where students recall answers to where teachers focus more on using the right questions, which will stimulate more critical student thought, inquiry, and reflection. Teachers need to focus on the right questions.

The Rigor/Relevance Framework introduces a second dimension of moving from the acquisition of knowledge to the application of knowledge. This is about moving from passive student work to engaging student projects. So the goal of good instruction is not only asking the “right questions,” it is about expecting the students to do the “right work.” Is that work relevant and leads to the learning objectives?

I recently changed my online course to add more authenticity to the work and avoid these educators from voicing the same question many students ask, “When will I ever use this?” The assignments in this online course are now identified as authentic projects. Students demonstrate learning through five projects, including developing a demonstration video, designing an instructional model, creating a schema as an instructional guide, and developing an online learning module for a selected audience. To be honest, there is one traditional paper to be written (it is still essential to request educators to continue elevating their writing skills).

As teachers work on reflecting on their instruction, just as I did in this course, there needs to be clear learning objectives (based on standards). Teachers must strive for high rigor and relevance by asking students the right questions and assigning the right work in authentic projects. This will go a long way toward moving education to greater relevancy and respect.