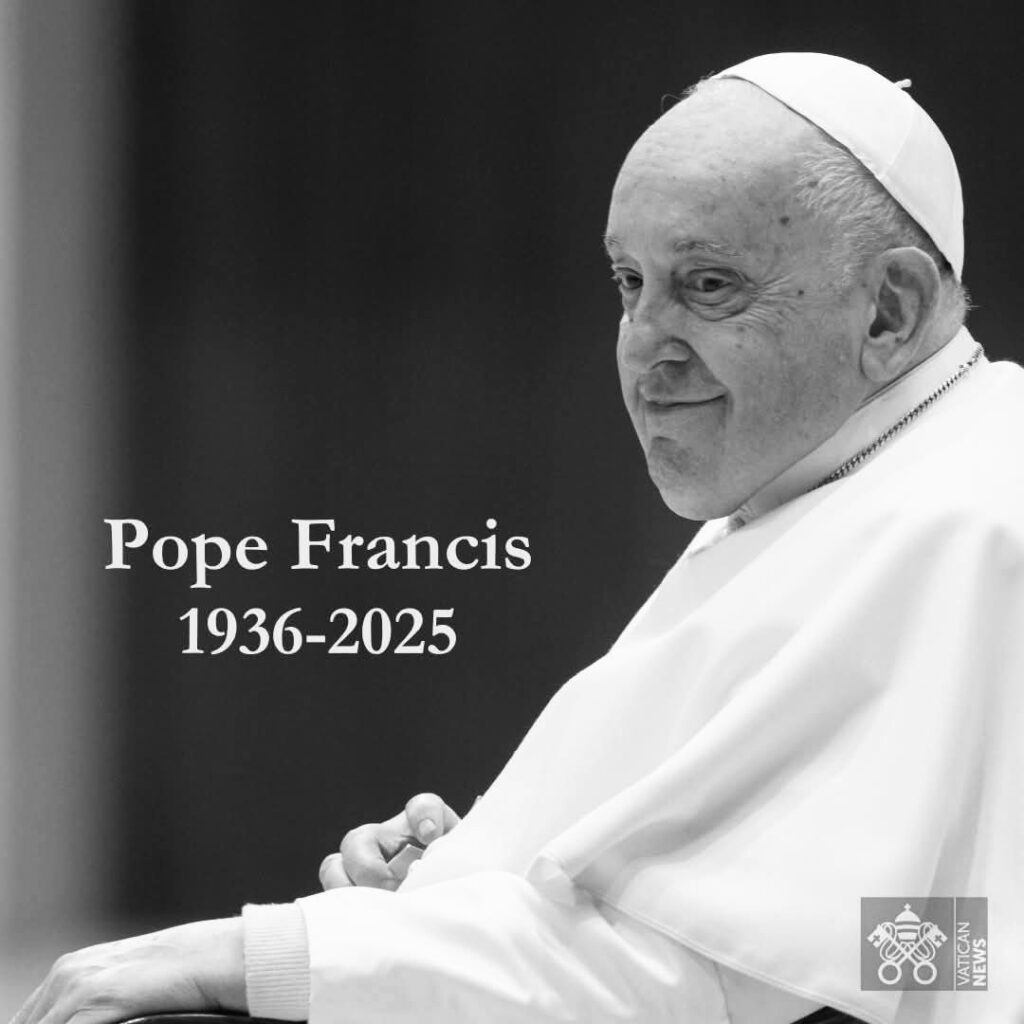

The death of Pope Francis and the news media tributes caused me to recall a blog I wrote 11 years ago when he was a relatively new Pope. Following is the blog I wrote comparing his behaviors to how leaders in a complex organization can change the organization. I still think my observation as a leader is on point, considering how he acted as Pope throughout his tenure. It will take more time to measure Pope Francis’s impact on the Catholic Church, but he has affected many people, as shown by the tributes. As I reread this old blog, I realized that some political leaders must adopt some of Pope Francis’ leadership behaviors.

Pope Francis – Model of a Leader in a Complex Adaptive System

by Dick Jones 12/19/2013

Jorge Bergoglio was tapped in March as the new leader of the 1.2 billion Roman Catholic people. In these few months, he has generated considerable “buzz” for his leadership style, both within the Catholic church and the greater public. His first act as Pope was to take the unique name of Francis, which broke from tradition and inspired a key role of the church in aiding the poor. Leadership in any organization is challenging, but in large, complex organizations like the Catholic church, leadership is even more challenging. The strict doctrines, formal hierarchies, and rich cultural traditions imply an organization that will not change. However, issues like declining membership, public attitudes toward religion, shortage of priests, and conflicts in values create a tension that the organization must address. How does a new leader deal with this apparent “rock and a hard place,” needing to change but needing to stay the same? The answer is exactly how Pope Francis behaved. The lessons here are leadership lessons for anyone who assumes a leadership role in a complex organization. I think, particularly in the American political and education systems, which are complex adaptive systems, we need more leaders who think and act like Pope Francis.

When leaders step into the role of a large complex organization, they tend to think they were selected for that position because they are the smartest person in the room, capable of making the difficult decisions to solve the complex current problems. There is a tendency for leaders to believe they are all-powerful and that they can command any change. Due to religious and personal beliefs, Pope Francis understands that he is not all-powerful nor all-knowing.

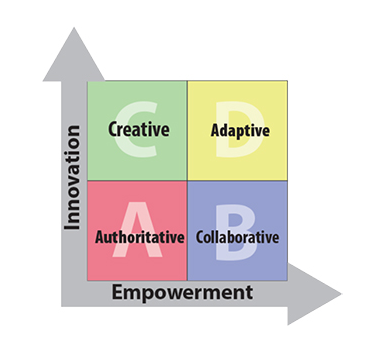

More and more researchers are examining complex adaptive organizations and the unique ways they change. A complex adaptive system is composed of a diversity of people or processes that interact with each other and mutually affect each other. The result of these complex interactions is an overall organizational behavior. However, the pattern of behavior in these systems is not constant because when a system’s environment changes, so does the behavior of its people or processes. In other words, the system constantly adapts to the conditions around it. Over time, the system evolves through continuous adaptation. An excellent description of research on leaders in complex business organizations is “Leading at the Edge: How Leaders Influence Complex Systems.” Regine, B., & Lewin, R. (2000). https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327000EM0202_02

Pope Francis exhibits effective leadership behaviors in complex organizations.

Model Ethics, Caring, and Concern

Complex organizations have the capacity to change themselves over time. For that organization to change in a positive direction, it is the leader’s role to affirm the core beliefs of the organization and a commitment to strong ethical behavior. The leader should seek to inspire stronger, more positive efforts on behalf of the organization. The leader’s statements must strongly affirm the leader’s commitment to ethical principles in moving forward. The leader needs to show that he is fully committed to the organization, and every person in the organization is valued. Nearly every action by this Pope reinforces that he is deeply committed to the church and values every person’s work, regardless of position. There is no talk of “cleaning house” and removing unethical bishops or immoral priests. All of the conversation is positive. Those changes will come, but will not be driven in a top-down, authoritative manner.

Push to the Edge of Chaos

When change is necessary, the leader must convey that it is not business as usual. During a leadership change, many people who are comfortable in the organization want to see stability. They want the new leader to act like the previous leader to maintain the comfortable status quo. Pope Francis has not done that. Actions such as living in simpler quarters, changing traditions in dress, and avoiding condemning homosexuality have people watching and paying attention. He is not making changes in the organization, but sends a message that things are different. That creates a bit of chaos, not totally disruptive, but heightens everyone’s focus within the organization. It adds an energy of excitement and anticipation. From that, energy changes are more likely to evolve within the organization.

Evoke Emotions

Complex organizations establish procedures and doctrines to follow and maintain consistency within the organization. These become the boundaries of acceptable behaviors. But procedures do not inspire new actions. They tend to maintain the current status quo. A church dealing with so many social issues needs new energy and direction. Leaders do this by evoking emotion. In complex people organizations, emotions drive change. Leaders who want to strengthen the organization must evoke positive emotions in people. It is not the new policy or procedure that inspires action; it is emotions. The things we care about trigger our emotions — family, children, people less fortunate, and the environment. Pope Francis’ actions, such as embracing the disabled man with severe facial disfiguration and his affection for children and the poor, trigger emotions in us that make us want to join him in the work of the church. It is not following a church doctrine; it is following a leader.

Make Small Changes That Have Powerful Effects

Complex organizations seem totally resistant to change, but it is actually the opposite. They resist large-scale change but are constantly changing and adapting throughout the organization. The leader has an effect by making small changes that ripple across the organization. Just as a stone thrown in a lake creates a small ripple that cascades across the entire surface, small changes can have big effects. One example from Pope Francis is the answer to a reporter’s question about homosexuality, a polarizing issue in the church. His answer was simple, “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?” He didn’t avoid the issue with a “No Comment.” He didn’t say we need to change the policy. He acted in a way that we should not condemn and castigate homosexuals. This ripple effect could significantly impact the church by modeling the behavior of treating everyone with respect, regardless of beliefs or behaviors.

It remains to be seen, over time, the lasting leadership impact that Pope Francis will have on the Roman Catholic church, but as a new leader, he clearly exhibits leadership behaviors that are valuable lessons for other leaders in other complex organizations