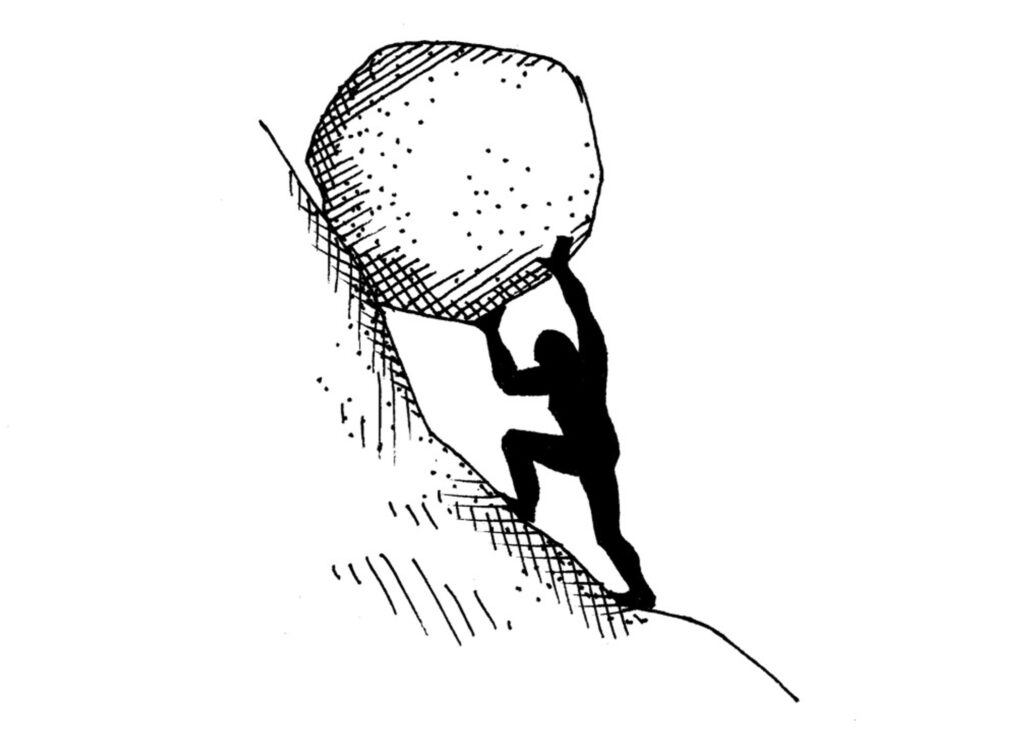

Teaching is challenging! Many times, at the end of the day, exhausted teachers wonder if they are making any headway in moving a reluctant student toward success. Having to repeat safety procedures, reminding students to replace their tools, or tutoring a student for the third time on multiplying fractions can create the unsettling feeling that learning is impossible. The Greek legend of Sisyphus comes to mind as an apt metaphor for this kind of frustrating teaching — endlessly pushing a boulder up a hill, never making any progress.

The boulder could well represent some of our students, who require considerable effort to push them to the place where we hope they will be, on the mountain of education achievement. The mental image of the weary teacher and a massive, impassive student boulder is not healthy for teachers or student learning.

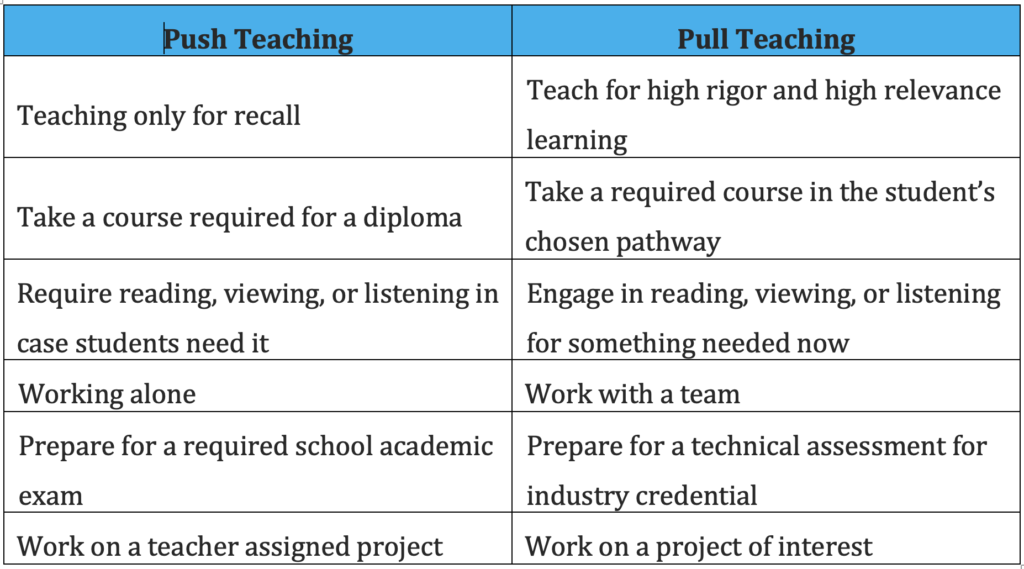

Working with reluctant learners feels like pushing students across the finish line of passing a course. Instead of thinking of teaching as a “pushing” exercise requiring considerable effort, reimagine it as pulling. Your immediate reaction might be, “Wow, pulling an object up a hill is even more challenging than pushing.” However, think about using an internal pull rather than thinking about an external pull of you trying to pull the boulder uphill. Shift the mental model of the teacher working externally to pull or push students toward a learning goal to one of facilitating the student’s internal pull toward that goal. This is the push and pull of student learning. Teachers pushing students to learn is exhausting and frustrating. In contrast, the feeling is very different when the student feels an internal pull to accomplish a learning goal. Setting up an internal pull still requires effort, and teachers may exert more time planning and facilitating learning. Still, the results are rewarding for students and teachers.

What drives our students? And how can teachers create an internal pull that motivates students? In his book Drive, Daniel Pink describes the three inner motivators that move people, in other words, that pull people toward a goal. Pink points out that it is not rewards and punishment that drive people; it is a shared purpose, frequent measurement of mastery, and the ability to make autonomous choices. First, we are motivated when we adopt a clear goal or objective, especially when we share that common purpose with others we care about. Second, when people can frequently measure that they are gaining proficiency in their work through frequent recognition, feedback, or even self-reflection, it drives them to continue to practice and improve. Finally, when people have greater autonomy in what they do, and when they do it, it increases their drive. These motivating principles apply to students as well.

Career and Technical Education offers some natural pull learning because the subject matter is usually not a requirement, students have some choice in what they study, and the courses have a clear, relevant purpose. Moreover, mastery is often visible because it is measured by performance in a real-world setting. That is why CTE students are generally more motivated than students in general academic courses.

Of course, even CTE teachers’ work can sometimes drift into feeling like teachers are pushing reluctant students to success rather than the learning goals pulling them toward success by their interest in the content. Teachers can rely less on pushing and facilitate more pulling by applying the Drive principles — shared purpose, frequent measurement, and autonomous choices — in a mental learning model.

A great way to think visually about push vs. pull learning is to use the Rigor/Relevance Framework™. The framework categorizes high and low levels of rigor and relevance. Low rigor/low relevance learning is what teachers seem to have to push students to complete. CTE is naturally highly relevant, but even CTE can sometimes become bogged down into low-rigor tasks. When students are challenged with real-world problems of high rigor and high relevance, solving that problem becomes a pull on student motivation. In these teaching situations, students will work to acquire the foundation knowledge of skills needed to solve the problem or construct the solution ultimately.

Think about your teaching. The more you can pull learning into your work with students, the more motivated they will be.

Try to include more pull in your CTE instruction, and at the end of the day, your instruction will seem less like the work of Sisyphus and more like the reason you became a CTE teacher.